Indagine sulle comunità faunistiche presso l’area di Bayan Onjuul, Mongolia

Primo aggiornamento

Referente della ricerca: Claudio Augugliaro (Green Initiative, Mongolia).

In collaborazione con: Fototrappolaggio S.R.L.

Il progetto verrà realizzato nel soum (unità amministrativa nella quale sono suddivise le regioni) di Bayan Onjuul che si trova nella steppa della Mongolia centrale. A 1.250 m.s.l.m. ha una superficie di 4.790 km2 e una densità di popolazione di 1,9 abitanti per km2, essendo così una delle aree meno densamente popolate del nostro pianeta.

La zona è di particolare interesse sia a livello naturalistico che sociale.

In tutta l’area certamente esiste ancora una numerosa presenza di specie della fauna vertebrata tipiche della regione Paleartica ma rare o estinte altrove, quali i carnivori come il gatto di Pallas (Otocolobus manul), la lince (Lynx lynx) e il lupo della steppa (Canis lupus chanco), gli ungulati quali l’argali (Ovis ammon) e lo stambecco siberiano (Capra sibirica), e gli uccelli come l’avvoltoio monaco (Aegypius monachus), il grifone himalaiano (Gyps hymalaiensis) e il falco sacro (Falco cherrug).

Tuttavia non è mai stata condotta una ricerca scientifica allo scopo di stilare una check list delle specie vertebrate, la quale segnalazione è affidata alle testimonianze locali, soggette a errori e condizionate dagli usi locali.

Nessuna operazione di gestione e/o di conservazione è supportata da basi scientifiche. Quest’ultimo aspetto è probabilmente riconducibile a difficoltà oggettive, ad esempio gli spostamenti per raggiungere tali luoghi remoti sono davvero complicati e costosi. Non esistono strade asfaltate e spesso è molto complicato trovare del carburante se non nelle tratte più frequentate (poche). Infine le condizioni del terreno gelato per gran parte dell’anno non aiutano certo a condurre una analisi approfondita, che possa essere basata sul rispetto di un rigoroso protocollo scientifico. In questo contesto uno studio effettuato attraverso il fototrappolamento, può soddisfare requisiti difficilmente raggiungibili in altro modo.

La durata del progetto è di 24 mesi nelle aree più indicate per una raccolta dati significativa, che sono la catena montuosa a cui si fa riferimento con Montagna Sacra “Zorgol Khairahan” e l’area di dune sabbiose di Arburd.

La catena della Montagna Sacra (Zorgol Khairahan) è caratterizzata da affioramenti di tipo granitico ed è l’unico grande complesso di questo tipo nel soum di B. Onjuul e dei soum limitrofi. Costellata da cavità più o meno ampie e vere e proprie grotte, rappresenta una opportunità di rifugio, per i numerosi mammiferi che qui sfruttano le tane e i ripari naturali.

L’area di dune sabbiose di Arburd, rappresenta un’isola ecologica nella quale vi sono presenti specie floristiche e faunistiche, proprie della comunità biologica di un sistema dunoso. L’area è l’unica superficie costituita da dune sabbiose, nel raggio di un centinaio di km. Considerato che la superficie non è particolarmente estesa, un protocollo di campionamento efficace può fornire un range completo ed esaustivo di dati per tutta l’area di dune, rilevando le probabili differenze nella composizione faunistica, rispetto alla comunità della steppa circostante.

Grazie all’ausilio delle fototrappole sarà possibile compilare una check list delle specie di macro e micro mammalofauna presenti nell’area, individuare eventuali migrazioni stagionali, comprendere i modelli comportamentali delle specie censite (periodi di massima attività giornaliera durante le diverse stagioni), verificare la presenza e l’abbondanza delle specie di carnivori, ponendo particolare attenzione alle specie minacciate quali il gatto di Pallas (Otocolobus manul) e l’Argali (Ovis ammon) essendo in decremento in tutto il loro areale di distribuzione ed estinti in alcune aree (secondo quanto riportato dalla IUCN, le specie potrebbero essere presto inserite nella red list come Vulnerabile). L’attività di foto-video trappolaggio verrà eseguita in collaborazione con la Fototrappolaggio srl che fornirà anche le strumentazioni necessarie per l’esecuzione della stessa.

Aggiornamento del 02/04/2014, autore: Claudio Augugliaro

Tra il 30 e il 31 Marzo 2014 sono state posizionate 7 fototrappole nella nostra area di studio.

L’area di studio di 20 km2 entro la catena di Bayangiin Uul (area nota come Montagna Sacra), e’ stata suddivisa in 20 stazioni di circa 1 km2 ciascuna. Per ciascuna delle stazioni verranno effettuati circa 120 giorni di fototrappolamento complessivi nell’arco di un anno.

Gli habitat selezionati entro le stazioni, includono affioramenti granitici a volte contornati da vegetazione arbustiva o erbacea e molto piu’ raramente è possibile siano presenti pochi esemplari arborei. Le fototrappole sono state posizionate ad una altitudine tra i 1350 m circa (poche decine di metri dalla steppa) e i 1550 m (a circa 200 m dal livello della steppa). Per il momento si è deciso di non recare alcuna forma di disturbo con flash, richiami olfattivi o vocali. Una delle fototrappole e’ stata posizionata di fronte a due piccole pozze di acqua che si deposita in una marmitta per scioglimento della neve. L’acqua sarà presente alcune settimane sino al prosciugamento, per poi tornare alle prime piogge di Giugno. Tra l’altro proprio in questa piccola marmitta sono costretti a passare gli ungulati per giungere ad una piccola grotta nella quale si rifugiano durante le ore diurne. Questa zona e’ praticamente inaccessibile al bestiame domestico, per il quale comunque vengono adoperate pozze e laghi presenti a livello della steppa. Soltanto in 2 delle 7 zone di posizionamento delle fototrappole, non sono state trovate tracce di bestiame domestico. Bisogna comunque considerare che I terreni da pascolo vengono sfruttati soltanto stagionalmente in conseguenza delle migrazioni dei pastori nomadi, che nell’area variano tra I 2 e I 25 km.

La prima verifica verrà effettuata a 45 giorni circa dal posizionamento delle fototrappole.

In seguito alcune foto dei luoghi nei quali sono state posizionate le fototrappole (non sempre la posizione esatta ma anche l’area circostante).

Qui si vede la foto trappola sull’albero

Dal punto in cui è stata scattata questa foto è stata piazzata una fototrappola

Secondo aggiornamento

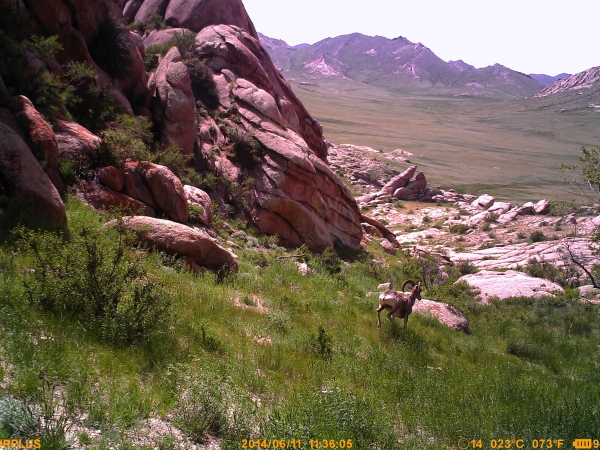

Fig. 1 – The photo above shows specimens of wapiti (Cervus canadiensis). Recently this group has been accepted as a separate species from C. elaphus, after a mitochondrial DNA analysis. The Wapiti are giants that can reach 600 kg (deer which occur in the Mediterranean are rarely reach over 100 kg). During the Pleistocene age, wapiti grazed on the steppes of Beringia, on the Bering Strait. At the end of the last ice age, Beringia was submerged by the ocean and the wapiti moved into North America and northeast Asia, forming separated populations.

The first 45 days of camera trapping can be deemed as a test for the placement of the cameras in the steppe environment, where difficulties can be encountered. Data can still be collected in this time to form the basis of hypotheses.

The best results have been obtained from placing the cameras in restricted passages, which can be found at the base of or on top of granite outcrops. In some cases, it is possible to find suitable canyons in such outcrops. Some Wapiti (fig. 1) have been recorded in open areas, where the passage of some ungulates was previously tracked. In this first sampling we preferred to not use scent to attract carnivores. However, no carnivores were detected. In past tests with 3 days of sampling using scent, several carnivores were recorded: wolf (Canis lupus chanco) and stone marten (Martes foina intermedia), both of which are subspecies distinct to central Asia.

Setting the mode to photo+video gave us the chance to identify various specimens and family groups.

Interesting data regarding the 3 large ungulate species occurring in the area were obtained: the Wapiti (Cervus canadiensis), the Argali (Ovis ammon) and the Siberian Ibex (Capra sibirica). Only one station had an adequate area for the passage of the three species. Specimens all three species used the passage to climb up a rock outcrop, between 6:00 am and 7:40 pm. The specimens probably went down to the steppe in the late evening to graze, but they never used the same passage as for getting up. These animals can move much faster in open terrain, and their passage was not recorded from 15 April to 5 May, during which time it snowed.

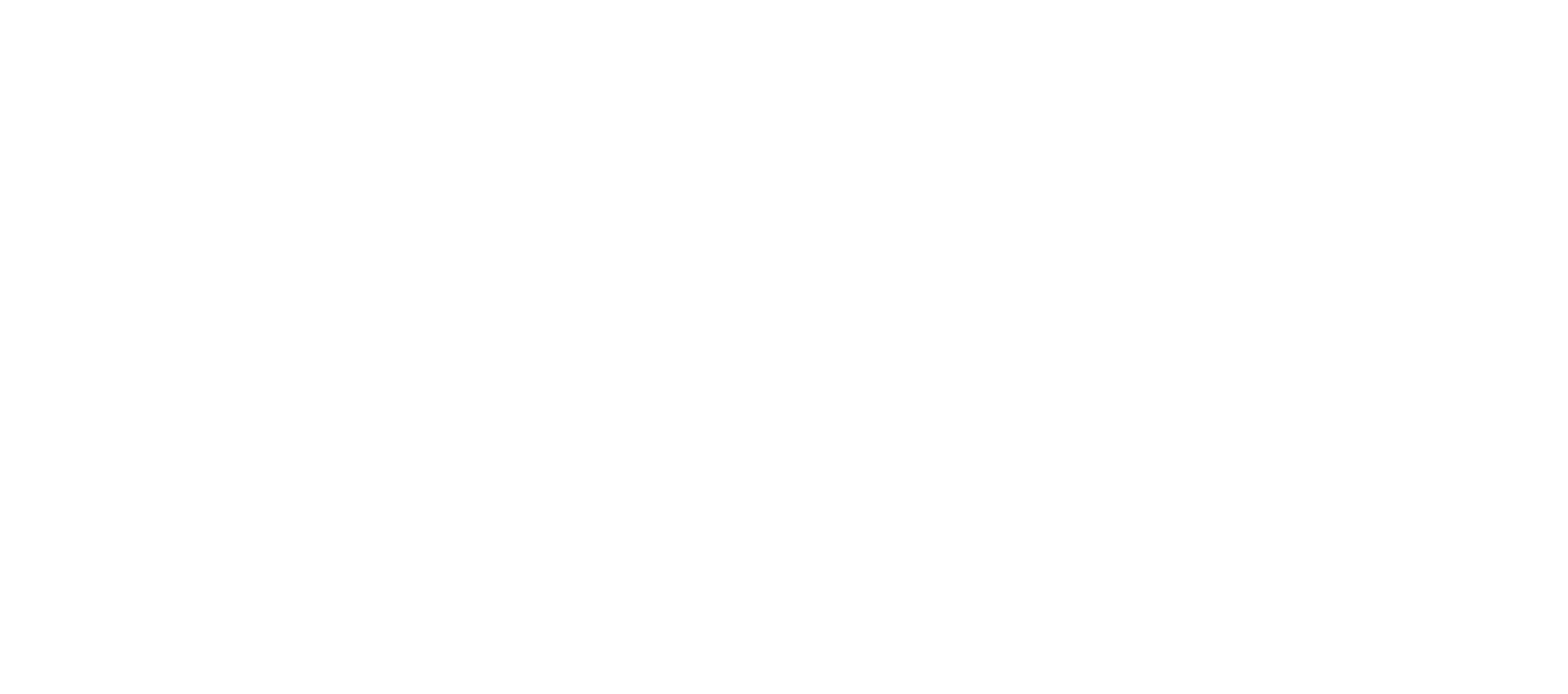

Three couples of adult Argali (Ovis ammon) with lambs (two couples with two lambs and one couple with one lamb) and probably two single adults were found at the granite outcrop. In Mongolia, the male argali weighs over 200 kg (five times more than Mediterranean wild sheep). It is possible that the specimens recorded all belong to the same group and the females are temporarily separated to raise their lambs born a few weeks earlier. For each specimen a distinctive sign has been found, for instance a broken horn or a pattern in the fur in the neck area. The specimen with a broken horn is likely a male. Two couples repeatedly used the passage many times from 13 to 15 April. At the moment it is too early to make a hypothesis on the reason for this high rate of passages in a so short a time. Previous studies found a population of 300 specimens in this area, which is believed to be accurate. The Bayangiin Uul outcrop is a very important refugee area for this central Asian species, which is listed as Near Threatened and is listed in Appendix II of CITES.

Fig. 2 – Argali (female) with lamb

Wapiti have been recorded in both the granite outcrop and in the open hills of the steppe. On 13 April a group of three males were observed who still had old antlers, which generally fall down in the late winter. The same specimens were recorded again later that day and had lost their antlers. They were recorded again 20 days later in the same area and had gotten new antlers covered with velvet.

The passage of a male without antlers and another with new antlers, and another four males with new antlers were recorded in the hilly area. It is impossible to determine if the same male was present in both groups.

More than 10 passages were recorded in the rock outcrop between 13 and 16 April. There were probably 4 to 6 individuals, and only one time were they recorded in a couple. Two were probably female as they did not have any sign of antlers, but the others were males with evident signs of the base of the antlers they had lost. Wapiti are not a widespread species in Mongolia, especially in the steppe (they are more common in the forest). Again in this case, Bayangiin Uul represents an important refuge for this species which is much more abundant here than in the nearby Khustai National Park (also home to Przewalski’s horse), which is less than one hundred km away.

Fig. 3 – Male specimen of Wapiti. Notice the mane, which is totally absent in the female.

Two specimens of Siberian Ibex were recorded in three instances, in the same day but 12 hours apart. In this case the identification was easy since one specimen had a broken horn. It is not clear what subspecies occurs in this region, either the Altai or Gobi subspecies. It is not recorded in distribution maps from the IUCN, but local biologists know about its presence. Bayangiin Uul represents the northeastern tip of its distribution area.

Fig. 4 – Siberian Ibex (Capra sibirica), with the left horn damaged. In Mongolia the male can be over 100 kg. It is the object of our study, because it is a victim of international trade due to its precious cashmere. Its main distribution area is in the Altai Mountains, while in the steppe it can be found only on granite outcrops over 100 m high. They are quite rare in the steppe.

These three species have an overlapping distribution area in Bayangiin Uul, though there are some differences in their habitat preference.

The camera traps have been placed in another 7 locations, fixed on trees (except for 2) and only in restricted passages at the base of a rock outcrop. Four stations have been equipped with scent to attract canids.

Terzo aggiornamento

Quarto aggiornamento